Adapting to the New Reality

For those who had spent their entire lives under the pull of Earth’s gravity, the transition to microgravity was more than just an adjustment—it was a reckoning. The first wave of independent space pioneers, scattered across low Earth orbit, found themselves caught between exhilaration and struggle. The dream of living free in space had become a reality, but the body was slow to accept it.

Some adapted quickly, reveling in the unshackled sensation of floating. These were the natural-born explorers, the ones who had spent their childhoods imagining themselves as astronauts, running simulations in virtual reality, or training in the few zero-G environments Earth had to offer. Others, however, were not as fortunate.

The first symptoms of space adaptation syndrome hit within hours—dizziness, nausea, disorientation. The human brain, so accustomed to the firm assurance of up and down, struggled to recalibrate. Stomach contents threatened to defy containment, and headaches pounded like a relentless drum. Some settlers, determined to push through, found themselves unable to hold down food, their bodies rejecting this new reality. Microgravity sickness wasn’t just inconvenient—it was dangerous.

Survival in the Void

The vessels themselves—rushed into service by a combination of DIY engineering and repurposed aerospace tech—were not designed for comfort. Every cubic meter of space was precious, every resource meticulously accounted for. Sleeping was an ordeal. Without gravity to press them into a bed, most settlers resorted to strapping themselves into small enclosures or makeshift sleeping bags. Those unprepared for the sensation of floating mid-sleep often found themselves waking in confusion, their bodies drifting aimlessly, sometimes crashing into equipment.

Food was another challenge. The pioneers had no luxury of fresh produce or gourmet meals—pre-packaged rations, nutrient pastes, and dehydrated food were their lifeline. Rehydration had to be done carefully, as liquid in microgravity formed stubborn floating spheres rather than pouring naturally. Improperly sealed water pouches led to a few minor but frustrating incidents where droplets drifted into sensitive electronics, shorting out equipment before repairs could be made.

Doctors and engineers worked around the clock to combat the challenges of muscle deterioration and bone density loss. Without gravity providing natural resistance, the body began to atrophy at an alarming rate. The answer came in the form of rigorous daily exercise, using resistance bands and anchored cycling machines. AI-assisted medical monitoring became essential, sending real-time health data to Earth-based support networks. The settlers were determined, but their bodies would only cooperate if given the necessary adjustments.

Psychological Isolation and the First Mental Health Crisis

Physically, they were adapting—slowly—but the mental toll of isolation proved to be a different kind of challenge. For the first time, humans were living completely disconnected from the world they had always known. Some thrived on the thrill of it, while others found themselves grappling with an unexpected loneliness. The vast emptiness outside their thin metal hulls was both awe-inspiring and terrifying.

Communication with Earth was still intact, but time delays and bandwidth limits meant settlers had to ration their contact. AI-driven personal assistants helped maintain routines, but there was no substitute for human interaction. Depression and anxiety began creeping into the orbital settlements, pushing some to their breaking points.

A psychological support network formed among the pioneers. Virtual meetups became a ritual, with settlers linking their spacecraft through encrypted peer-to-peer networks—a decentralized, AI-regulated system beyond the reach of corporate or governmental oversight. They shared stories, played games, and even held music sessions, using their fragile radio connections to stave off the void’s crushing silence. Mental resilience became just as vital as physical endurance.

First Lessons of Space Living

As the weeks passed, the settlers adapted. They learned to move with precision, pushing off walls with calculated force to avoid collisions. They reconfigured their ships’ layouts, creating rotating duty schedules to prevent exhaustion. They experimented with small-scale hydroponic food systems, seeking ways to grow edible plants despite limited resources. They found new ways to make space livable, even if it meant rewiring old assumptions about how life should work.

The dream of space was no longer just about getting there. Now, it was about learning how to stay.

The Supply Problem

Survival in space wasn’t just about the body—it was about the resources that kept it alive. Independent space travel had given pioneers the freedom to escape Earth’s control, but now they faced a new, ruthless reality: the vast emptiness of space offered nothing for free.

Unlike government-backed missions with tightly coordinated supply chains, these rogue settlers had no logistical safety net. Every gram of food, every liter of water, and every watt of energy had to be meticulously managed. It didn’t take long for the first shortages to appear.

The Water Crisis

Water, the most precious resource in space, was running dangerously low on some vessels. While modern spacecraft were equipped with recycling systems, turning urine, sweat, and condensation back into potable water, the efficiency varied. Some ships had high-grade closed-loop filtration, while others—especially those built on scavenged or modified tech—found their systems degrading faster than expected.

Desperate crews turned to trade, bartering RLUSD and XRP for shipments of water from Earth-based suppliers willing to break regulations. Smugglers, operating through encrypted financial channels, delivered clandestine shipments to those who could pay. Meanwhile, engineers worked on refining their water recovery processes, knowing that a single failure could mean death.

Food Shortages and the First Space Farms

Food was no less urgent. The pioneers couldn’t rely forever on Earth-based shipments, especially as corporate-backed security forces began enforcing economic restrictions. Supply runs were becoming more expensive, riskier, and subject to external control.

Some settlers turned to hydroponic and aeroponic farming, growing algae, fungi, and select vegetables in microgravity. Early experiments yielded mixed results—light exposure, nutrient balance, and water distribution required careful management. Yet, the most determined engineers refused to fail. The first fully functional space farm was assembled aboard a linked cluster of rogue ships, a fragile but crucial step toward self-sufficiency.

Power Struggles: The First Energy Crisis

Energy was another battle. While solar panels provided consistent power, they weren’t invulnerable—damage from micrometeoroids and debris forced frequent repairs. Some settlers experimented with small-scale nuclear reactors, but these were dangerous and controversial, requiring intense safeguards. Others devised energy-sharing agreements, forming the first decentralized space power grid—an independent network of peer-to-peer energy exchanges, leveraging smart contracts built on blockchain technology.

The Birth of the Orbital Black Market

With shortages came opportunity. The first space-based black market took root, running entirely on cryptocurrency. Rogue engineers modified communications arrays to create encrypted trade networks, allowing ships to barter food, water, and supplies without corporate oversight.

What had started as a desperate scramble for survival was now becoming something more—an independent space economy, separate from Earth’s control. But this growing system had drawn the attention of powerful interests. And soon, the corporations would make their move.

First Orbital Habitats

The transition from scattered vessels to a functional orbital society was neither planned nor structured—it was driven by necessity. Independent settlers, once content to float through the void in their isolated ships, soon realized that survival in space required cooperation. The first true orbital habitats were not grand space stations designed by governments or corporations; they were makeshift clusters of linked vessels, cobbled together by necessity and ingenuity.

The First Settlements

The earliest pioneers took advantage of modular docking ports, fastening ships together into sprawling, patchwork networks of pressurized corridors, repurposed cargo bays, and converted storage modules. What had once been a scattered fleet of independent craft became an interlinked network—fragile, prone to malfunctions, but alive.

Oxygen, water, and power could now be shared, allowing settlers to pool their resources instead of struggling alone. Some ships specialized in food production, others in mechanical repairs, while a handful served as crude medical bays. What began as necessity soon evolved into an informal barter economy, a decentralized exchange of services and materials that kept the settlements running.

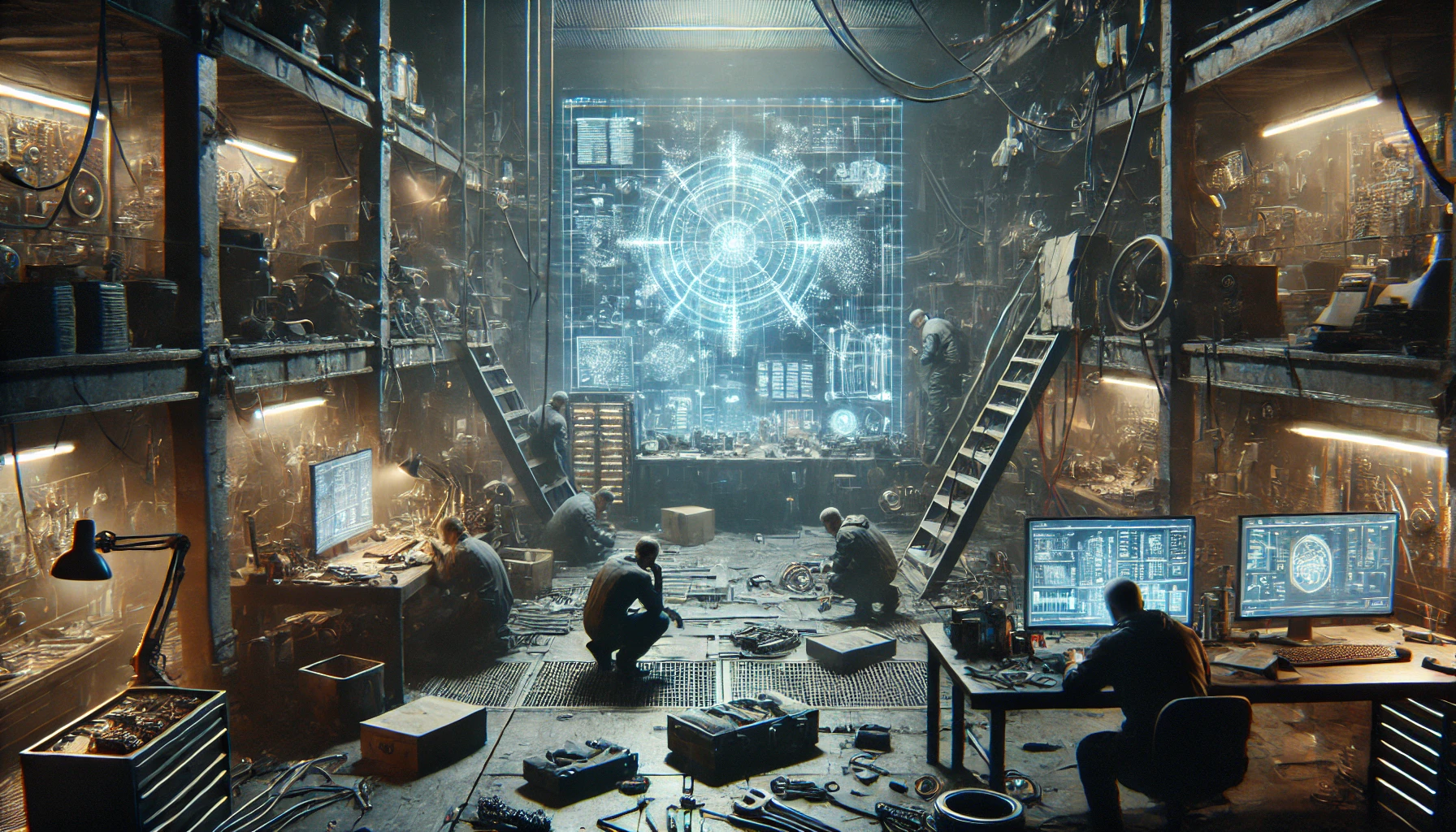

Engineering the Future

As these orbital clusters expanded, engineers took on the challenge of making them sustainable. Recycled materials from defunct satellites, discarded space debris, and even salvaged corporate wreckage were repurposed into structural reinforcements. Some pioneers experimented with artificial gravity, testing small rotating modules to mitigate the long-term health effects of zero-G. Others sought to develop rudimentary shielding against radiation, layering their vessels with composite materials designed to absorb and disperse cosmic rays.

Every innovation was hard-earned. Space was unforgiving, and failures were costly. The settlers who worked on structural modifications knew that a single miscalculation—a seal failure, a decompression event, or an electrical short—could spell disaster. But the alternative was stagnation, and for those who had left Earth behind, progress was the only path forward.

Emerging Leadership and Conflicting Ideals

Without any centralized authority, governance was an afterthought—until it wasn’t. Disagreements over resource distribution, docking rights, and safety protocols began surfacing as the population grew. Some settlers pushed for voluntary coordination, proposing self-imposed guidelines to prevent accidents and disputes. Others resisted, wary of any structure that might evolve into control.

Factions began to form. The Libertarians—those who believed absolute independence was paramount—argued that each ship should maintain full autonomy, only participating in trade and shared resources on their own terms. The Cooperatives, on the other hand, saw the need for structured agreements, advocating for a loose but binding set of laws to protect the settlements from internal strife and external threats. The tension remained unresolved, simmering beneath the surface as settlements continued to grow.

First Contact with the Corporations

For a time, the orbital pioneers believed they were beyond the reach of Earth’s influence. They were wrong.

The first corporate survey drones arrived unannounced, silently mapping the settlements and transmitting data back to their parent companies. Not long after, corporate representatives attempted to make contact, disguising their intentions as offers of aid and cooperation.

Some settlers welcomed the dialogue, seeing potential benefits in trading with Earth-based corporations for advanced supplies. Others were suspicious, aware that the corporations had no intention of simply coexisting with independent settlers. The first attempt at corporate negotiation ended with a stark realization—these settlements were not viewed as equals or pioneers. They were seen as obstacles, liabilities, or assets to be acquired. A warning had been delivered, even if unspoken: The corporations were watching. And they would not allow a rival society to thrive uncontested.

The First Collision Incident

It was bound to happen. With dozens of independent vessels maneuvering in close proximity, the first major space collision was only a matter of time.

The Warning Signs

Navigation in low Earth orbit was a delicate balance of velocity, trajectory, and limited fuel reserves. With no centralized traffic control, each vessel relied on its own calculations and AI-assisted guidance to avoid disasters. But the reality was far from perfect—outdated software, hardware failures, and human miscalculations created a chaotic and unpredictable orbital dance.

Aboard the Gideon’s Wing, a small repurposed cargo ship linked to one of the orbital settlements, engineer Malik Orlov was running routine diagnostics when the warning klaxon blared.

“Unidentified vessel on collision course. Impact in twenty-six seconds.”

Panic surged through the crew. The ship’s AI rapidly calculated escape maneuvers, but it was already too late—the approaching craft, a modified deep-space mining vessel, had lost maneuvering thrusters and was spinning uncontrollably.

The Impact

The collision wasn’t a direct hit, but it was enough to tear through Gideon’s Wing’s external hull, breaching one of its docking modules. The impact sent both vessels into an uncontrolled tumble, forcing nearby ships to engage emergency thruster burns to avoid secondary impacts.

Inside, chaos erupted. Atmosphere vented from the damaged sections, sending unsecured equipment—and one unfortunate crew member—spiraling into the void. Emergency bulkheads slammed shut, sealing off the breach, but the damage had already been done. Gideon’s Wing was crippled.

The mining vessel, equally damaged, drifted helplessly, its crew trapped inside with failing life support. With no rescue protocols in place, it was up to the settlers to decide whether to intervene or let the doomed ship drift into oblivion.

A Risky Rescue

Despite the risks, an impromptu rescue operation was launched. Two independent vessels dispatched EVA teams, their crews navigating the debris field with limited oxygen and unstable propulsion packs.

The situation was made worse by the fact that neither ship had standardized docking interfaces—rescue teams had to cut their way into the wrecked mining vessel, manually depressurizing compartments to prevent catastrophic decompression.

After nearly two hours of coordinated effort, all four crew members were extracted, though one was critically injured. With Gideon’s Wing still crippled, survivors were shuttled to a nearby station for emergency care.

The Aftermath: Calls for Coordination

The incident sent shockwaves through the independent space community. For the first time, the fragility of decentralized space travel was fully realized. There were no rules, no safeguards—just the raw dangers of spaceflight.

Some settlers argued for a voluntary coordination network, a system where ships could share navigation data to avoid similar disasters. Others, however, resisted, fearing that such a system would be the first step toward centralized control—and eventually, corporate domination.

In the end, no consensus was reached. The community remained divided, with some ships adopting informal navigation pacts while others maintained strict independence.

But one thing was clear—the frontier was not a safe place. And with growing numbers of vessels in orbit, this wouldn’t be the last catastrophe.

Corporate-backed Security Forces Intervene

The corporations had been watching. The collision incident had proven what they already knew—independent space settlers lacked coordination, structure, and, most importantly, oversight. It was only a matter of time before they stepped in.

First Signs of Corporate Involvement

At first, it came under the guise of assistance. A convoy of corporate-owned security vessels, emblazoned with the logos of Lunacore Industries and Stratus Dynamics, arrived in orbit, broadcasting messages of “safety enforcement” and “mutual cooperation.” They claimed they were there to help prevent future incidents, offering enhanced navigation systems and emergency response protocols.

Some settlers saw an opportunity. These were established aerospace corporations with advanced technology, promising stability and safety. Others, however, knew better. Help came at a cost.

The Unofficial Blockade

Within days of their arrival, the corporations began setting up “restricted zones” in orbit—areas where only registered ships were allowed to pass freely. Independent vessels found themselves subject to mandatory inspections, fines, and sudden restrictions on movement.

A new pattern emerged—ships that complied were granted access to fuel shipments and supply caches. Those that resisted found their supply routes cut off.

The corporations weren’t using weapons to control space—they were using infrastructure.

Stealth and Defiance

Some settlers refused to submit. Ships began going dark, switching off their transponders and navigating manually to avoid detection. Others resorted to countermeasures—black-market navigation scramblers, AI-assisted route optimizers, and encrypted trade channels that bypassed corporate surveillance.

The first stealth convoys were organized—independent traders moving vital supplies under the radar, evading corporate patrols. The corporations responded by deploying more advanced tracking algorithms and covert drones designed to flag rogue movement.

A game of cat and mouse had begun. And for the first time, orbital space was no longer just a frontier—it was contested territory.

The First Stand-off

Tensions reached a breaking point when a small independent trade vessel, The Horizon Dawn, was intercepted by a corporate security ship. Its captain, Elias Raines, refused to comply with a forced inspection, claiming his cargo was private property.

The corporate vessel responded by cutting off the ship’s ability to dock at any corporate-controlled resupply stations, essentially blacklisting it. No fuel. No repairs. No access to critical trade hubs.

In retaliation, a dozen independent vessels rallied together, offering Horizon Dawn a lifeline—refueling in defiance of corporate control. The act of defiance sent a clear message: they would not be controlled.

A Battle Brewing

The corporations had tried to integrate the settlers into their system. Now they were beginning to realize that control would not come easily.

For now, there were no direct conflicts, no battles in the void. But the first fractures had formed.

And war, even if still unspoken, was beginning to take shape.

The First Corporate Betrayal

For a brief moment, it seemed like cooperation might be possible. Some settlers, weary of the growing tension with corporate forces, attempted to negotiate trade agreements. They figured that if independence was impossible, perhaps coexistence was the next best option.

They were wrong.

The Deal That Went Sour

A group of independent traders, led by former aerospace engineer Jonas Tellar, struck a deal with Stratus Dynamics, one of the most powerful corporations operating in orbit. The agreement was simple: in exchange for compliance with corporate regulations, Stratus would provide logistical support, fuel, and medical supplies to participating ships.

The settlers, hoping for stability, agreed. They registered their vessels, accepted corporate oversight on supply exchanges, and even allowed Stratus Dynamics to install security beacons on their stations. What they didn’t realize was that they had just signed away their autonomy.

The Corporate Trap

Within weeks, the terms of the agreement changed. Stratus Dynamics began demanding increased oversight, placing new restrictions on movement and trade. Fuel costs doubled overnight, medical supplies became scarce, and priority docking privileges were revoked unless additional “service fees” were paid.

What had started as cooperation had turned into extortion.

Jonas Tellar and his traders protested, demanding that Stratus uphold the original terms of the deal. The corporation’s response was swift: communications were cut, access to supply lines was revoked, and a formal notice was issued stating that all Stratus-affiliated settlers would be required to reapply for access—this time under full corporate employment contracts.

The Turning Point: The Seizure of Outpost Helios

Realizing they had been played, the betrayed settlers took drastic action. A small group of them—armed with cutting torches and reprogrammed drones—seized an abandoned orbital facility known as Outpost Helios, cutting off its corporate access codes and repurposing it as a rogue supply hub.

Stratus Dynamics immediately denounced the act as piracy. Corporate security ships were deployed, but without a clear mandate to use force, they could only circle the outpost, broadcasting warnings. Inside, the settlers worked quickly to fortify their position, hacking the station’s systems to reroute power and secure its life-support functions. Outpost Helios became the first fully independent stronghold in orbit.

The Fallout

The betrayal of Stratus Dynamics sent shockwaves through the orbital community. Even those who had previously supported corporate cooperation now saw the truth—there was no peaceful co-existence. The corporations weren’t interested in partnership. They wanted control.

In response, more settlers cut ties with corporate supply chains, turning instead to the growing cryptocurrency-driven black market. Rogue engineers began modifying navigation systems to avoid corporate surveillance, while others focused on stockpiling resources, preparing for what many feared would be an inevitable escalation.

For the corporations, this was only a temporary setback. They had suffered a minor loss—but now they had an excuse. The settlers had “attacked” corporate property. And soon, retaliation would come.

The settlers had taken their first real stand. Now, they would have to face the consequences.

Preparing for the Moon

The corporations had made their move, and the settlers had answered. Orbit was no longer just a frontier—it was a battlefield of control, trade, and survival. But for the most ambitious pioneers, staying in low Earth orbit was never the goal. The Moon was the next step.

The Dream of Lunar Expansion

Independent engineers and rogue scientists had been studying the problem for months. Lunar landings weren’t just a question of propulsion; they required sustainable life support, radiation shielding, and reliable resource extraction.

Despite the challenges, the dream of a lunar colony was no longer fantasy. Settlers had already identified potential landing sites—lunar lava tubes offering natural protection from cosmic radiation, crater rims that provided continuous sunlight for solar power, and frozen deposits of water ice that could be harvested for survival.

But the corporations were watching.

Testing the Limits of Technology

With limited funding and no government oversight, settlers turned to decentralized innovation. Small, experimental landers were constructed, using modified thrusters and reinforced shielding. DIY engineering took center stage—3D-printed heat shields, repurposed carbon-composite hulls, and AI-assisted trajectory calculations became the foundation of the first independent lunar missions.

The first unmanned test lander—codename Pathfinder-1—was launched from an orbital settlement, its destination a preselected crater on the Moon’s southern pole. For six agonizing hours, engineers monitored its progress. Then, as the lander approached lunar orbit, something unexpected happened.

The First Lunar Interception

Without warning, a corporate drone—unregistered and unidentified—altered its course. It intercepted Pathfinder-1 mid-flight, disabling its telemetry. Within minutes, the lander’s signal was lost.

The message was clear: the corporations would not allow an independent presence on the Moon.

Outrage spread through the settlements. The corporations had no legal claim to the lunar surface, yet they had acted as if space belonged to them. Settlers debated their next move—some argued for an immediate retaliatory mission, while others called for patience, demanding a more calculated response.

But one thing was undeniable—if the settlers wanted the Moon, they would have to fight for it.

A Defiant Response

The destruction of Pathfinder-1 didn’t stop the settlers—it only strengthened their resolve. Underground networks formed, pooling resources to build a second lander, one designed to evade corporate surveillance.

This time, it wouldn’t be an unmanned test. A human crew was preparing to take the risk.

They knew what was at stake. The corporations had drawn the line. Now, the settlers had to decide whether to cross it.